WRITING HELP

Click to set custom HTML

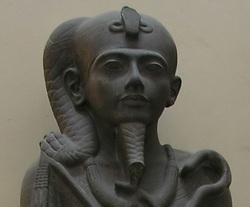

Hatshepsut

- Traditionally, king was male, identified as a manifestation of a male god, the falcon-headed Horus.

- Publicly, therefore, Hatshepsut was most often depicted as a male king in the prime of life.

- She rarely appears as a woman in either statuary or relief carving.

- Wearing

the traditional kilts of a king and a variety of crowns, she is shown

in her reliefs striding forward and reaching out, where a female figure

would have stood passively, feet held close together by an ankle-length

dress, usually with her arms at her sides or bent back toward her body

- In

representing herself as male, Hatshepsut was not being deceitful; she

was simply conforming to the conventions of royal representation

- As one of two kings existing at the same time, Hatshepsut was a senior co-regent to her nephew Thutmose III

- For a reigning king to take a younger co-regent was a well established tradition, dating back at least to the Middle kingdom.

- However,

by depicting herself in the familiar role of the older of two

simultaneously reigning kings, she reinforced not only her nephew's

legitimacy but her own.

- A number of women had ruled Egypt before Hatshepsut.

- Most of them ruled as mwt nswt, "King Mother," an important title from the very beginning of Egyptian history.

- Kings

often died young, leaving very young sons as successors, and because

an adult serving as regent might be tempted to seize power for himself

before the child came of age, tradition soon assigned the role to the

young king's mother, who would presumably gladly yielded power to her

own son.

- Thus, of the early kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty, probably only Thutmose I cam to the throne as an adult.

- Ahmose,

Amenhotep I, and Thutmose II seem to have been quite young at their

accessions, perhaps averaging five years old, which means that their

mothers or other female relatives ruled for ten to twelve years before

they came of age

- As a result, women effectively ruled Egypt for almost half of the approximately seventy years preceding Hatshepsut's accession.

- The acceptance of these women's rule and their veneration after death surely helped legitimize Hatshepsut's kingships.

- In

contrast, to King's mothers, who were honored for generations

afterwards, queens regnant were persecuted after death: their names

obliterated, their monuments destroyed

- While

apparently, her initial instinct was to rule in the name of Thutmose

III, she could not do this officially because she was not his mother.

- That

title belonged to a woman named Isis, a secondary wife who did not have

independent ties to the royal family as Hatshepsut did.

- That

she did not step down after her co-regent was of age has been taken as a

sign of Hatshepsut's ambition, but in fact it is hard to imagine how

she could have done so.

- A coronation in ancient Egypt was no mere ceremonial occasion: its rituals literrally transformed the new king into a God

- Once

Hatshepsut took the steps to make herself a king, and hence also a god,

both she and Thutmose III were committed to joint rule until her death,